Abstract

A work of art can embody multiple rights: those of the artist, those of the purchaser and, in certain cases (if we confine the analysis to Italy), even those of the Italian State. These latter rights are intended to safeguard the national artistic and cultural heritage, but they may extend to the point of limiting the free circulation of the work.

In this article, we shall take our cue from a real and widely debated case to analyse the stringent rules imposed on owners of works of art of particular value and the related sanctions in the event of non-compliance. We shall also close with some practical advice.

The limit on exporting works of art

Imagine owning a painting acquired years ago — perhaps received as a gift from a relative, from the artist personally or from a friend, or inherited. Suppose that, over time, the work has increased in value. One then decides to sell it, to donate it, or simply to move it to one’s home abroad. This seemingly innocuous and legitimate act of disposition can be prohibited by the Italian State itself.

For certain works, it is compulsory to request and obtain a Certificate of Free Circulation, without which they cannot lawfully be exported. This is not an exceptional measure, but the straightforward application of the rules. Let us illustrate them through a case which — now a decade ago — sparked debate.

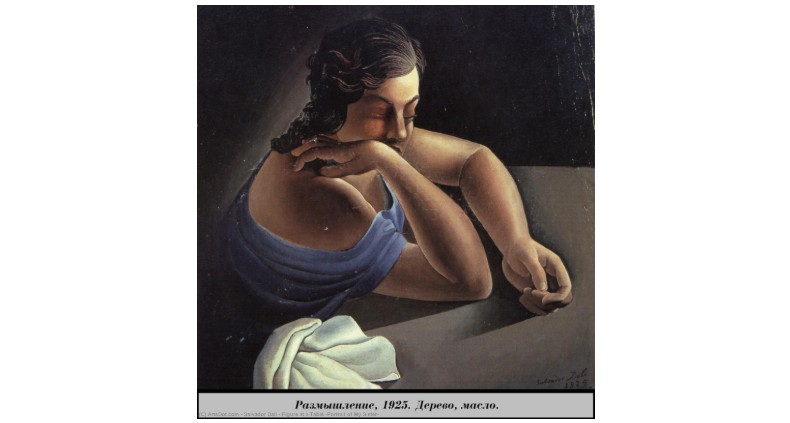

Figure at a table (portrait of my sister), Salvador Dalí, 1925

We are speaking, of course, of Salvador Dalí’s Figure at a table (Portrait of my sister), portraying the artist’s sister. The painting, owned by the collector Elena Quarestani, was destined for Christie’s abroad, and there was also interest from the Gala Foundation (covered at the time by The Guardian: ‘The reasoning was crazy’ – how Italy blocked the sale of a Dalí painting).

That transfer would have entailed the work’s departure from Italian territory, but — under the Cultural Heritage and Landscape Code (Legislative Decree 42/2004) — the work fell within assets of cultural interest subject to export restrictions. Under this system, the owner must obtain prior authorisation for export; only once the certificate has been issued may the work lawfully leave the country.

It is an extremely restrictive framework that protects the national heritage while directly affecting individual rights; failure to comply with the prescribed steps is not without consequence: sanctions can be severe, even criminal in nature.

The Dalí case epitomises an increasingly topical conflict: public protection of cultural heritage vs private freedom to dispose of one’s works of art. The protective legislation is complex and merits closer examination.

How to export a work of art

The procedures for exporting a work of art vary according to two factors: the type of departure (definitive or temporary) and the destination (within or outside the European Union).

For the definitive export of contemporary works (created less than 50 years ago or by a living author) a self-declaration of contemporary art (AAC) suffices, which permits free circulation.

The constraints, however, increase with the age and the value of the work.

- Works between 50 and 70 years (author no longer living): a declaration must be filed with the competent Export Office.

- Works over 70 years and valued at under €13,500: a simplified exit declaration is required, valid for six months.

- Works over 70 years and valued at over €13,500: it is necessary to obtain a Certificate of Free Circulation (Article 68 of the Code) and, if the work is destined outside the EU, an Export Licence (Article 74).

If one intends to take the work out of Italy only for a short period (up to 18 months) — for example for an exhibition, an event or restoration — it will be sufficient to request a temporary authorisation (Articles 66 and 67). If the work has already been declared of cultural interest, prior authorisation from the Ministry of Culture is required (Article 48).

In the Italian legal system, selling and exporting a work of art is not merely a commercial act: it requires balancing the right of ownership with the protection of the national cultural heritage.

Sanctions under the Italian Cultural Heritage Code

Breaches of the rules on the protection and circulation of works of art can be severe, going beyond administrative penalties. The Code provides a range of remedies from an order to reinstate the asset through to criminal liability.

First and foremost, violations hit one’s pocket.

In addition to administrative fines, the authority may order reinstatement of the asset at the responsible party’s expense: this means bearing restoration, expert appraisal, transport and storage costs — often higher than the penalty itself.

If the work can no longer be traced, compensation equal to its value becomes payable — a line item capable of turning a mere procedural irregularity into an outlay equal to 100% of the price.

Perhaps the most delicate aspect for those wishing to sell abroad is the nullity of acts concluded in breach of prohibitions or without the prescribed authorisations. Nullity means the act produces no effects: the buyer does not become the owner and the seller must return the price received.

On top of this come, as a rule, costs and damages: transport and insurance, commissions, duties, installations and — if necessary — the costs of return and documentary regularisation. With a foreign purchaser, nullity founded on Italian overriding mandatory provisions renders the act ineffective under national law in any event.

Criminally speaking, unlawful export or failure to return after a temporary export constitute offences, punishable by custodial and pecuniary penalties, and confiscation of the asset is envisaged (including confiscation of equivalent value). This profile adds to — and does not replace — the civil sanctions just described.

How to protect oneself? The answer is obvious: comply with the applicable rules. Clearly, this necessarily entails informing oneself beforehand, taking action well in advance, and involving professionals with a solid background in the field.

Compliance as the key to reducing risk

Before selling, donating, or even merely transferring a work of art abroad — perhaps to one’s second home — it is essential to carry out certain preliminary checks. Italian law attaches great importance not only to the material ownership of the work, but also to its cultural significance.

The first step is to ascertain the age of the work and the identity of the author. If the artist is living or the work is recent, the “export” procedure is relatively simple: a self-declaration will suffice for free circulation.

If, however, the author is no longer living and the work is more than fifty years old, it is prudent to consult the competent Export Office to determine whether it is subject to limits or authorisation requirements.

Another decisive aspect is the assessment of economic value. Once the €13,500 threshold is exceeded, the asset may be subject to stricter authorisations and direct oversight by the Soprintendenza; it is advisable to engage an expert or art valuer to obtain an official, documented appraisal.

It is also important to retain all documentation regarding provenance — invoices, certificates, deeds of gift, succession papers, exhibition catalogues — since these materials help demonstrate lawful possession and simplify administrative formalities. Every transfer of ownership or across a border should be accompanied by a copy of the certificate or authorisation issued.

Finally, before proceeding with any transfer, even if not for commercial purposes, it is always advisable to consult a lawyer or consultant specialised in art law. Prior knowledge of the constraints and the necessary authorisations can avoid costly mistakes and sanctions, ensuring that the work remains protected, valued and held in compliance with the law.

© Canella Camaiora S.t.A. S.r.l. - Tutti i diritti riservati.

Data di pubblicazione: 29 Ottobre 2025

È consentita la riproduzione testuale dell’articolo, anche a fini commerciali, nei limiti del 15% della sua totalità a condizione che venga indicata chiaramente la fonte. In caso di riproduzione online, deve essere inserito un link all’articolo originale. La riproduzione o la parafrasi non autorizzata e senza indicazione della fonte sarà perseguita legalmente.

Gabriele Rossi

Laureato in giurisprudenza, con esperienza nella consulenza legale a imprese, enti e pubbliche amministrazioni.